Four and six coupled on sugar mill tramwaysBy John KnowlesFrom Light Railways No.148, August 1999

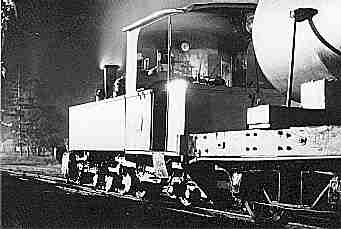

North Eton Mill's Hudswell Clarke No. 1 (496 of 1898) was built as an 0-6-0ST with a long wheelbase to fit the third axle behind the firebox. Could this have contributed to the broken axle which has brought it to grief? Photo: John Browning collection courtesy Ron Swindells In his article in Light Railways 141, Bruce Belbin raises interesting questions about this subject. He says that those who ordered locomotives for government owned or sponsored mills believed that, for a slight loss of adhesive power in an 0-4-2T, the advantages of a trailing truck gave an engine which was easier on the track, able to take sharper curves, rode better and ran faster, especially when running in reverse delivering empties. It has always surprised me that so many 0-4-2T locomotives were built for Queensland sugar mills: consider the rosters of Tully, South Johnstone, Mourilyan, Babinda, Inkerman, Plane Creek and Pleystowe. And that is for engines which could have been 0-6-0T or 0-6-2T, disregarding the small 0-4-0T type. It cannot have been that the 0-4-2T engines were ordered first and regretted later, because except for Tully they were ordered over a long period. On the other hand, many six coupled engines were ordered by other mills (some 0-6-2Ts), again over extended periods, while CSR clearly favoured six coupled. It is specially interesting that Tully, owner of five Fowler 0-4-2Ts from prewar, obtained two Perry 0-6-2Ts postwar. Generally, both four and six coupled engines on the 2 ft gauge had the firebox behind the rear coupled wheels, even 0-6-0Ts, allowing a grate wider than the distance between the frames. That in turn allowed easy dumping of ash, and entry of underfire air. (A notable exception were the Hunslet 4-6-0Ts, which had a grate between the frames, and the frames themselves between the wheels.) Generally, too, even the largest 0-6-0Ts, had short rigid wheelbases, and took sharp curves happily. Although there were sharp curves on the mill lines, they were not especially numerous. There was no reason why coupled wheels could not be the same diameter on both four and six coupled types, so that both could run at the same speed for the same cylinder efficiency and mechanical wear and tear. Both types had such wheels of 24 to 28 inches diameter on both 0-4-2T and 0-6-2T types. A rear truck, with some control over its sideways movement (centering springs or swing links, the latter shown in the Perry plan in Light Railways 141), would have steadied the rear end and improved the ride, but there were rear trucks on both four and six-coupled types. Very little vertical springing was possible on such trucks, and little effect of it felt in the cab. In any case, the rear end still swung around to the extent of the overhang from the rear coupled axle; the side control of on the rear truck simply dampened the severity of the swing. Easier on the track? Hard to say. Both types had, or could have had, compensated springing, but it remains unproved that compensated springing helped the track. Had the six coupled types been harder individually on the track, that might have been balanced overall by the heavier loads they hauled through greater adhesion. Or they might have been easier on the track because they could obtain all the adhesion needed for the output of their boilers and cylinders with lighter axle loads. The lower adhesion of an 0-4-2T compared with an otherwise identical (except for wheel spacings) 0-6-0T could be expected to have considerable consequences for the load the engine could haul. Generally, effective tractive effort cannot exceed a quarter of the weight on the coupled wheels. In the presence of cane trash, and perhaps for light axle loads in any case, perhaps one fifth might be the best that could be achieved. And for a cane tramway, the ability to haul the greatest possible load towards the mill would be expected to dominate everything else - speed with empties, crew ride, effect on track - to the extent that these were measurable effects in any case. (To say that Mourilyan number 7 was used on empty hauls seems odd - that means it would have returned light from taking out empties, and another loco would have had to go out light to bring in the fulls. If the latter was going out light, it would not have been much of a burden to take out the empties, and overall crew and locomotive running costs would have been less.) I have no figures for the weight distribution across the axles of any Queensland mill engines. I should expect from the axle locations that an 0-4-2T would have had at most about 75% of the adhesive weight of an "identical" (in the sense above) 0-6-0T, but might well have had the same as that of an "identical' 0-6-2T. (This "guessing" allows for a loco of 15 tons, with the rear truck carrying three tons where used; differences in weight from the number of axles are ignored.) From what is known about the weights of the various engines, it is hard to see that the choice between four and six coupled could have been influenced by track or bridge loadings. I can think of only two reasons why the four coupled might have been preferred. The first is that on inclines of any length the steaming capacity of the boiler was the main constraint, and that capacity could be made into effective tractive effort through four coupled wheels; i.e. there was no need for six. The second is that even if there was a sacrifice in absolute haulage ability, the four coupled engines had sufficient haulage ability for the loads offering at the mills which bought them, prior to about 1940. In both cases, there would have been some saving in initial purchase costs and maintenance cost in a four coupled engine compared with a six coupled, although that cannot have been great in the total costs of cane haulage. The several histories of the sugar mills have paid little attention to the technicalities of the tramway systems. Do records exist saying why the engineers and/or managers at the various mills preferred particular sizes, wheel arrangements and weights for locomotives? Further accounts of experience on the road, and of traffic originating on various lines, especially at mills with both four and six coupled engines, would be of great historical value.

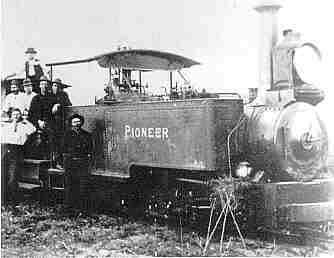

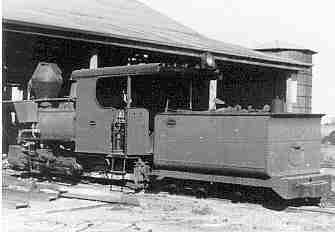

The John Fowler 0-6-0T design dominated the mill fleets at the turn of the century. Mossman Mill's PIONEER (8047 of 1899). Photo: John Browning collection

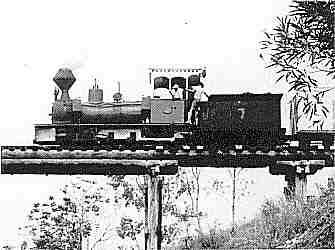

Hudswell Clarke captured the CSR market with their 0-6-0 tender locomotive. Gin Gin Mill's 7 (1098 of 1915) had originally been delivered to the nearby Childers Mill and is here running onto Boundary Creek bridge with empties as it travels the regauged QGR branch to the east of Wallaville in the 1960s . Photo: Brian Webber

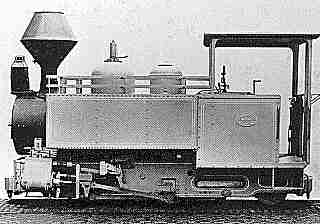

Moreton Mill's John Fowler 0-6-OT EUDLO (16207 of 1925) was an exception to the rule, a tank locomotive without a trailing axle built in the interwar years. Here it heads cab-first along Howard Street towards the mill in August 1961. Photo: Brian Webber

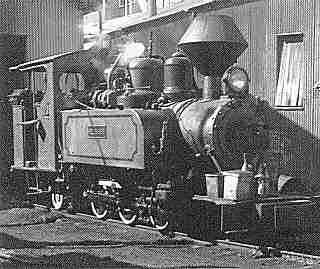

Mossman Mill's John Fowler 0-4-2T IVY (15947 of 1922) was poweful for its size but reputedly a rough rider. Photo: Rural History Centre, University of Readiing and some further thoughts...By John BrowningBruce McDonald and Gerry Verhoeven have put their heads together and comment that while an 0-4-2T was kinder than an 0-6-0T while running in reverse, it was much more difficult to rerall following a mishap, and certainly had less of its weight available for adhesion. They suggest that as the government sponsored mills had a propensity for 0-4-2T locomotives, the issue might be one of culture, with technical thought of a certain kind dominant among the consulting engineers used by government and perhaps some private milling companies. Mike Loveday points out that the tendency is for the weight of a locomotive to be thrown away from the direction of travel. Photographs of Moreton Mill locomotives often show them running bunker first up Howard Street with loaded trucks to the mill, but many other mills seem to have made a usual practice of running smokebox first with the load, and in reverse with empty trucks. On the mill and Shire lines around Mossman there were many turning angles, and locomotives were normally turned to run smokebox first on every occasion. Mike points out that the 1923 Fowler 0-6-0T design with 8-1/2in x 12 in cylinders and 24 inch driving wheels and independent suspension (WEMBLEY at Mossman Mill, COOLUM and EUDLO at Moreton Mill) rode remarkably well at high speed, while a contemporary 0-4-2T locomotive with the same cylinder and driving wheel dimensions, and with independent suspension, (IVY at Mossman Mill) had very poor dynamic balance, giving a boneshaking ride. However, other larger Fowler 0-4-2T locomotives with 9-1/2in x 12 in cylinders and 28 inch driving wheels were a joy to drive at Mossman, Mulgrave, Mourilyan and South Johnstone. In relation to the Perry 0-4-2T at Mourilyan being used mainly for the haulage of empties, I do not know. However, it is interesting to note that when I visited Fiji in 1994, the practice was for locomotives to run out with empties at the start of the day, and to make a further foray for loaded trucks some considerable time later, resulting in extended periods of idleness as can be imagined. This seems likely to be a throwback to earlier industry practices when labour was relatively plentiful and therefore cheap and rolling stock expensive and thus in short supply. Remember that whole stalk cane does not require to be crushed within a few hours as is the case for chopped cane, so a more leisurely pace of transit to the mill was far more acceptable in days gone by (and remains so in Fiji today).

One could have been forgiven thinking that with the delivery of Baldwin 2-6-2T FELIN HEN (46828 of 1917) to Fairymead Mill in 1940, a particularly suitable wheel arrangement for the sugar industry had been found. This did not prove to be the case, and in 1956 the front pony truck was chopped off. Photo: courtesy Jim Longworth

The postwar Perry and Bundaberg Foundry locomotives were mostly of the 0-6-2T design. Here Marian Mill's Perry (2601.51.1 of 1951) rests on dual gauge track at the mill while QR molasses bombs are loaded in the early 1970s. Photo: Brian Webber A recent article in the Industrial Railway Record, (Harper, R., "Some Aspects of Industrial Locomotive Design" Industrial Railway Record 157, June 1999), points out that as gauge decreases, the maximum possible speed drops considerably. Stability at speed is important and carrying wheels are useful in increasing stability, allowing a reasonable speed on poor track and faster speeds on good track. The effectiveness of the suspension used is also a very important factor in this equation. Running in reverse with the trailing truck leading may have reduced the punishment on the track when travelling fast with empty cane trucks. The CSR 0-6-0 locomotives also ran in reverse with empties, and in this case the tender probably helped guide the locomotive into the curves. From the earliest days of cane tramways, locomotives with trailing axles were used, with a number of four coupled and six coupled types by British, American and European builders in evidence over the years. In 1893, Fowler settled on an 0-6-0T design which dominated the market for almost 15 years. However, a survey of types shows that after the introduction of the 0-6-2T by CSR in 1907, Fowler supplied very few of the larger types of cane locomotives without a trailing axle, with the exceptions including WEMBLEY, COOLUM and EUDLO, and a number for the QGR's Innisfail Tramway. CSR obtained a couple of Hudswell Clarke 0-6-0T locomotives In 1911 and when demanding a more powerful 0-6-0 tender type from Fowler at the same time, found them very reluctant to oblige. Instead, Fowler supplied 0-6-2 locomotives (which soon had their trailing axles amputated) and it was Hudswell Clarke who successfully took over the CSR business with their very well known 0-6-0 tender type introduced in 1912. I believe that after 1911, the concept of the trailing axle for tank locomotives was almost universal among sugar mills. The choice between 0-4-2T or 0-6-2T probably related to overall size, weight and haulage power as well as to the maximum desirable rigid wheelbase length. It seems to me that most 0-4-2T locomotives were smaller than most 0-6-2T locomotives. In either type, the trailing axle was probably kinder to track and allowed a better balanced locomotive by enabling an axle to be placed behind the firebox, even if adhesive weight was thereby reduced. The introduction of rigid-framed 0-6-0 diesel locomotives in the 1950s certainly had very serious adverse effects upon track, and mills were forced to upgrade standards to accommodate them. The advantages of the bogie diesel locomotive, once accepted, were soon seized upon, but the innate conservatism of the sugar industry has been evident throughout the diesel era and no doubt was a very significant factor during that of steam also.

In 1927 Racecourse Mill wanted a suitable engine to haul cane over the newly built connecting link from the former CSR Homebush Mill tramway, and they received a Fowler 0-4-2 (17683 of 1927 with tender 17684). Photo: Brian Webber |